OPINION: ON THE $9BN AWARD AGAINST NIGERIA – LESSONS NIGERIAN POLITICAL LEADERS MUST LEARN

By Zik Gbemre

We have often wondered why Nigeria is often times in the news for the “wrong reasons”, than it is for the right reasons – when it comes to issues it faces as a nation, just like other nations too. Incidentally, most of the challenges facing Nigeria are often times, avoidable. But our “indifferent” and “I don’t care” attitudes towards very serious issues that affect the fabric of our wellbeing and growth as a nation, has always landed us in trouble. The sad part is that we often take this bad attitude towards governance and the way we do business as a nation, to the international scene, where people are very serious-minded. And this has never favoured us as a nation.

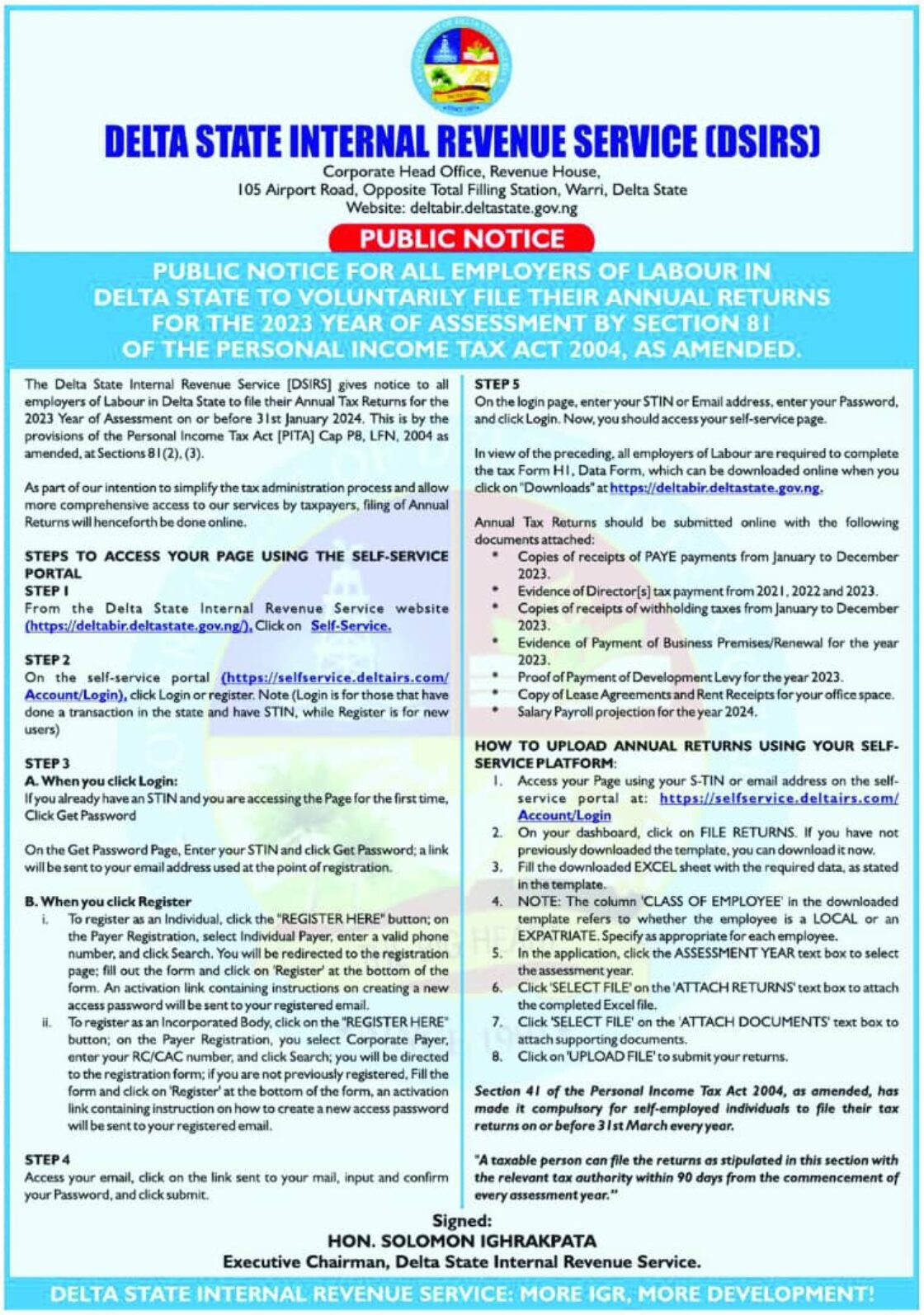

With our economic indicators not inspiring any hope that things will get better soon, and our debt to revenue ratio approaching above 70%, We were appalled and greatly troubled even more with concerns for the fate of the Nigerian economy, when recent reports revealed that a British commercial court has imposed $9Billion damages or fine against the Federal Government of Nigeria for violation of contract obligations with an Irish Engineering and Project Management Company – Process and Industrial Developments Limited (P&ID). Aside the fact that this calls for extreme sober reflection, it is also a strong threat to our national fiscal sustainability, considering the fact that the $9Billion is about the same value as revenue generated and accrued to the federal treasury in the 2018 fiscal year. Though, the said award was made as far back as July 2015 by an arbitration panel sitting in London, what happened in London recently was a failed legal move by Nigeria to stop the enforcement of that judgment. That means if this gets to be implemented, Nigeria’s bank accounts in the UK, where parts of our foreign reserves are warehoused, would be at risk, and that would be a catastrophe for our international trade.

Recently, the Federal Government had stated that it will prosecute everyone linked with the said contract that resulted in the judgment of the United Kingdom, Business & Property Courts (the Commercial Court) which awarded the stated cumulative sum of $9bn award against Nigeria and in favour of P&ID. This was made public by the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of the Federation (AGF), Abubakar Malami, who questioned the sincerity of those behind the contract awarded in 2010, as he argued that it formed part of the inglorious legacies of past administrations, which this government is being made to grapple with.

According to a news writer with a leading tabloid, Simon Kolawole: “although Nigeria is fighting tooth and nail to stop the enforcement of what is easily one of the largest arbitration awards in human history, anyone familiar with the entire fiasco knows that we are fighting a tough battle. We are primarily basing our objection on the fact that Nigeria is a sovereign state and “has an absolute right to obtain an authoritative determination of its sovereign immunity”. Put another way, we are arguing that we have immunity as a sovereign nation — and therefore the judgment cannot be enforced against us. We are also arguing that P&ID did not fulfil its own part of the contract and cannot, therefore, be making any claims on us.”

In our usual lackadaisical manner, it happened that: “in January 2010, the federal government entered into a 20-year gas and supply processing agreement (GSPA) with P&ID to build a gas processing facility. The company was to process the gas for local consumption and for export while Nigeria was bound to supply the gas feedstock through building a gas supply pipeline to terminate at the location of the gas processing plant. One hundred and fifty million standard cubit feet (mscf) of gas per day was to be supplied to P&ID plant and gradually increasing up to 400mscf per day in the later stages of the project. Eventually, Nigeria defaulted and did not build the gas pipeline while P&ID did not invest a kobo in the project. But the company later initiated proceedings for loss of potential income and revenue which after so many years of back and forth, culminated in the award”.

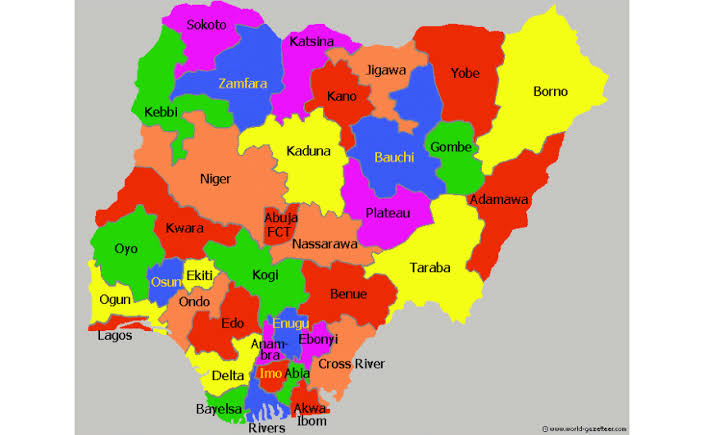

It is worthy to note that under the agreement, Nigeria was to receive 85 per cent of the refined non-associated gas, free of charge, for power generation and industrialization. P&ID would receive the remaining 15 per cent and the by-products – namely methane, propane and butane – which it would export. Nigeria would also benefit from the export proceeds through its 10 per cent stake in P&ID. Again, the GSPA required the government to build a gas supply pipeline to the P&ID facility to be located in Adiabo, Odukpani LGA, Cross River state. The gas was to be sourced by the government from OMLs 67 and 123 operated by Addax Petroleum. And this was where everything began to go wrong, as Nigeria did not build the pipeline like we said. P&ID said it had spent about $40 million on the project and the failure of Nigeria to build the gas pipeline had breached the agreement. The crisis went unresolved and in August 2012, the company activated the arbitration clause, filing a case of breach of contract against Nigeria in London.

“P&ID sought a compensatory award for loss of “potential” income. Nigeria argued that P&ID was supposed to have acquired the land in Cross River and built the processing facility before the government could build a gas pipeline to site. The company, however, argued that Article 6(b) of the GSPA did not state any such precondition. Apparently, the federal government had not shown any seriousness in building the pipeline and P&ID too had started foot-dragging. With the way the arbitration was going against Nigeria, the federal government started making moves to settle the dispute out of court. Offers were made to P&ID to that effect.

“P&ID agreed to accept $850 million in compensation, negotiated down from an initial proposal of $1.5 billion by a government committee. The payment was to be made in four batches — $100 million at first and then in three instalments of $250 million each. These were in the last days of President Jonathan, who had lost his re-election bid. He still wanted the figure reviewed downwards, but decided to leave matters for in-coming President Muhammadu Buhari. However, the Buhari administration, without a cabinet in place, did not follow up. P&ID then got the award in July 2015 — $6.6 billion for “loss of income” over the lifespan of the GSPA and $2.3 billion in interests.

“In fairness to Buhari, when he came in, Nigeria’s economy was already on its knees. Oil prices were down, there was forex crunch and states were owing salaries. The last thing on his mind was an $850 million payment for a project that never was. It seemed somebody whispered to Buhari to ignore the settlement agreement because of the “PDP factor”. That was a very wrong approach, I would say. If Buhari did not like the figure, he could have further negotiated it down. Nigeria is a sovereign entity and agreements are binding on all administrations. The P&ID guys complained that they waited in vain for Nigeria’s phone call, so they continued with the arbitration and got the huge award.

“Nigeria is said to be doing everything possible to make sure the judgment is not enforced. P&ID had instituted “recognition and enforcement” proceedings in the UK and the US. It won in both jurisdictions and this would allow them to seize (“attach”) Nigeria’s assets in both countries. However, Nigeria filed objections in the UK and the US on the basis of the country’s sovereignty. P&ID asked the US court to dismiss Nigeria’s objection as “frivolous” but the court has refused to do so, which gives us a ray of hope. Sadly, the English court dismissed Nigeria’s objection, which means the award can be enforced in the UK.”

While we are certain that they will surely appeal, there are indeed lessons our political leaders must learn from this situation. The first one is that the Nigerian governments must stop entering into contracts and obligations they are not ready to implement. This was noted by another public affairs writer on the subject issue. Nigeria is notorious globally for not respecting the sanctity of contracts, much less the rule of law. Investors always complain about our historical culture of impunity. Unfortunately, we can behave anyhow within our territory but there is civilization outside there and we cannot escape it. Evidently, too, there is lack of patriotism in some of the agreements’ government officials sign. There is no personal liability when things go wrong. Heads don’t roll. People don’t go to jail. The attitude is like: whose money is it, anyway?

We should realize that our lack of respect for the sanctity of contracts ends in our jurisdiction. Other countries and partners, whether public or private, take themselves very seriously and do not enter into frivolous contracts they are not ready to implement. Signing a contract and announcing it to Nigeria add no value to the local economy or the security and welfare of Nigerians without the requisite will to implement the same. It is also believed that the government officials packaging the business would not have any opportunity for private gain if the contract is not implemented. To stop this trend involves the design of processes that ensure the buy-in of every ministry, department or agency and stakeholder necessary to guarantee the implementation of the project. This will involve high levels of public- consultation and engaging the private sector to ensure that the project is not swept under the carpet.

The second issue is that every new government in Nigeria sees itself as not bound by agreements and obligations entered into by the previous government even when the two governments come from the same political party and one handed over to the other. For instance, that a contract was signed by the Umaru Yar’Adua government, of which Goodluck Jonathan was the deputy. There can be no excuse for the abandonment of the contract after the demise of President Yar’Adua by the Jonathan administration, considering the fact that the need for gas gathering and processing for local consumption and export remains pivotal to the overall development of Nigeria. Discerning Nigerians will recall that President Olusegun Obasanjo’s National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy led to the few achievements of his administration and before he left office, NEEDS 2 was at an advanced stage when virtually all stakeholders had been consulted and NEEDS 2 awaited a few inputs at the highest level to get it ready for implementation. But as soon as Yar’Adua took over power, he abandoned NEEDS 2 for his Seven-Point Agenda. This was done despite the fact Obasanjo virtually handpicked and installed him as President.

One major problem we have as a nation, is the lack of “Continuity” in Government at all levels. The end of any administration in Nigeria, is the automatic end of all pending projects/programmes and what have you. And that is why this subject issue was neglected by successive Governments till date, because there is no culture of continuity, and following up to complete what has been started by previous administrations. Every Government wants to outshine the other by coming up with their own projects and programmes. Not that anything is wrong with that, but Governance should be made progressive, especially in addressing projects that could outlive an administration’s lifespan.

To stop this attitude, we need the Project Continuity and Implementation Act which will bind governments to continue and fully implement existing projects before staring new ones. To abandon an existing project or to stop the same, the government must show cause and reason(s) using empirical evidence, to justify that the project is no longer in the overall national interest and thereafter, the government would be duty bound to bring the process of the project to a closure either through negotiations or requisite settlements that will close the file of the project.

The third issue is that Nigeria has been signing agreements where all the penalty clauses are tilted against the country and we have little or no protection whilst all the benefits from the agreement accrue in favour of the other parties. This is not the first time we signed such agreements. How on earth did we end up signing an agreement that entitles a company to claim loss of earnings without having invested a kobo? Who was the lawyer that drafted the agreement and how much was he paid? Was it a private legal practitioner or a team of lawyers in the Ministry of Justice? Who reviewed the draft to make inputs? Did the company use its lawyers to produce the agreement and simply asked the representatives of the Nigerian government to sign? When the blind and or ignorant leads their colleagues or even persons who can see, they are bound to enter a ditch if they are under obligation to follow wherever they go. Nigeria has produced enough quality legal practitioners and scholars of national, regional and international repute, professional jurists of the highest learning, character and reputation; to fall for this kind of blackmail is the worst thing to happen to this country.

To stop this madness, we need to have a system of using our best lawyers and jurists to draft and perfect agreements of this nature and to defend our legal disputes. Poor lawyering was responsible for our loss of Bakassi to Cameroon. Again, we did not use our first eleven for that case. And now, this one. Poor lawyering is caused in Nigeria by tribalism, favoritism, and corruption. There are indeed very bright and intelligent lawyers who can research and compile such cases like this, and do very well to protect the interest of the Nigerian Government. Sadly, when it comes to getting the best brains to do this, the issue of tribalism and what have you comes in to ruin everything.

Nigeria now needs to move expeditiously, in a targeted manner and in the national interest to engage the company before our assets are seized. We could possibly ask the company to come back and we start constructing the requisite gas pipeline and fulfil our own part of the obligation. Alternatively, we can negotiate the award and see how we can reduce it to a minimum. It would not be an easy negotiation but we cannot afford to sleep over this.

Zik Gbemre.

September 2, 2019.

We Mobilize Others to Fight for Individual Causes as if Those Were Our Causes